Temperature is one of the strongest drivers of semiconductor reliability. As junction temperature rises, failure mechanisms accelerate and mean time to failure (MTTF) drops, often exponentially. In high power-density systems, even small temperature reductions can significantly extend device lifetime and reduce field failure risk.

Key Takeaways

- Higher temperature dramatically shortens semiconductor lifetime.

- MTTF is often modeled with the Arrhenius equation, which shows that reliability decreases exponentially with temperature.

- A common rule of thumb: a 10°C increase can roughly halve lifetime.

- High power-density devices are especially vulnerable because they generate more heat in smaller footprints.

- Lowering junction temperature can improve lifetime, reduce early-life failures, and stabilize long-term performance.

What is MTTF and Why It Matters

Mean Time to Failure (MTTF) is a reliability metric that estimates the average operating time before a device experiences failure. It’s most often applied to non-repairable components such as semiconductor devices and ICs, where “failure” typically means the part no longer meets electrical or performance requirements.

MTTF matters because it connects device physics to real-world outcomes: warranty risk, system uptime, total cost of ownership, and safety margins. Engineers use MTTF to evaluate design tradeoffs (like operating temperature, power load, and cooling strategy), and to estimate how long devices will survive under specific conditions. In many cases, thermal stress is the largest controllable factor, making temperature reduction one of the most effective ways to increase reliability without changing the device itself.

Reducing junction temperature by even 10–25°C can dramatically extend lifetime. If your system needs higher reliability at high power density, JetCool’s patented microconvective cooling® technology can help.

Semiconductor Accelerated Life Testing

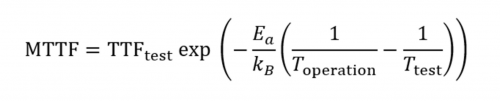

Usually, semiconductor manufacturers determine a device lifetime by an accelerated life test (ALT). Essentially, this means they pick a temperature for the device to operate, and measure how long the device runs at this temperature before it fails. In this case, failure is typically defined by a certain percentage decrease in performance. The temperature at which they test is usually much higher than the recommended device temperature so the device will fail on a time scale that they can actually see (hence accelerated life test). The results of the test are fed into the following equation, called the Arrhenius Equation, which allows us to approximately predict the lifetime of a semiconductor device:

where MTTF is the mean time to failure of a device operating at temperature T_operation, TTF_test is the lifetime of the device measured in an accelerated life test at temperature T_test, k_B the Boltzmann constant, and E_a is the apparent activation energy. The apparent activation energy E_a is a fitted parameter representing the dependence of lifetime on temperature, often specific to a given semiconductor material.

Now, this is a highly simplified formulation to predict device lifetime. There are some well-documented reasons to apply caution when using this equation [1,2]. Predicting your device lifetime with high accuracy would require a very thorough study for each individual device you want to characterize.

However, this formulation can show us general trends, particularly that device operating temperature has a significant effect on device lifetime. Let’s take a look at a plot of lifetime plotted against temperature to develop some intuition on this. For the purpose of illustration, we’ll apply parameters of an example gallium nitride (GaN) device of TTF_test=7E10 hours at T_test=127°C, at an activation energy of E_a=1.7eV. An interesting note here: the lifetime from the datasheet 7E10 hours is around 8 million years, where GaN devices have been around for maybe 10 years. The actual life test must have been done at a much higher temperature than what is listed, but the listed conditions correspond to the actual life test via the Arrhenius equation.

Note that the y-axis is logarithmic. What we see is the lifetime changes by a factor of ≈1E15 in the typical range of temperatures we may see from an electronic device. However, this plot has quite a range – let’s zoom into a section near where GaN devices are typically operated and convert it to a linear scale to get a better feel for what smaller changes in temperature may mean.

On this linear scale, we can clearly see the strong sensitivity to temperature. By increasing the device temperature by just 10°C, we have reduced the lifetime by over 2x. You may have heard a rule of thumb along the lines of a 50% lifetime decrease for each 10°C increase in channel temperature; that seems consistent with this formulation at this point in the Arrhenius curve. Even more significant, by increasing the temperature by 25°C from 225°C to 250°C, the lifetime dropped by almost an order of magnitude. This is equivalent to going from a ≈500 year lifetime to a ≈50 year lifetime on these devices, which will make operators of this device very happy if the lifetime ranges are a few times longer than a standard technology cycle.

How Thermal Management Reduces Reliability Risk

In practice, temperature is one of the few reliability drivers engineers can actively control. By reducing junction temperature, thermal management directly slows the physical failure mechanisms that limit semiconductor lifetime, which extends MTTF without changing the device, materials, or operating voltage.

Effective cooling lowers average junction temperature, reduces thermal gradients, and minimizes temperature cycling, all of which contribute to longer device life and more predictable performance. This is especially important in high density compute applications, where traditional air cooling often struggles to remove heat fast enough to prevent accelerated aging.

JetCool’s direct-to-die and on-chip integrated liquid cooling solutions are designed to address these challenges by removing heat closer to the source with much higher heat flux capability. By maintaining lower and more uniform junction temperatures, these solutions help reduce reliability risk, improve lifetime projections, and enable higher performance within the same thermal limits.

References

(1) O’connor, Patrick DT. “Arrhenius and electronics reliability.” Quality and Reliability Engineering International 5.4 (1989): 255-255.

(2) Hakim, Edward B. “Reliability prediction: is Arrhenius erroneous?” Solid State Technology 33.8 (1990): 57-58.